I don’t feel that I can say much about the most recent series of unarmed black people murdered by armed white people in uniforms which others have not already said better. I defer to Ta-Nehisi Coates on the subject.

But friend and blogfather Sean Treacy referred me to this paper about the history of American policing. After describing how police forces in the North evolved out of community watches and private, for-profit constable services, Potter moves south. As often happened, things went differently in the nation’s most distinctive region. As generally holds, they did so thanks to the needs of slavery:

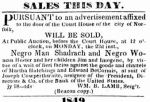

In the Southern states the development of American policing followed a different path. The genesis of the modern police organization in the South is the “Slave Patrol” (Platt 1982). The first formal slave patrol was created in the Carolina colonies in 1704 (Reichel 1992). Slave patrols had three primary functions: (1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside of the law, if they violated any plantation rules. Following the Civil War, these vigilante-style organizations evolved in modern Southern police departments primarily as a means of controlling freed slaves who were now laborers working in an agricultural caste system, and enforcing “Jim Crow” segregation laws, designed to deny free slaves equal rights and access to the political system.

Police forces, North and South, further evolved not to fight crime, but rather to combat public disorder as perceived by local businessmen. In the South this meant as Potter says above. In the North, it meant breaking strikes called, for convenience, riots. In both cases it meant outsourcing the cost of protecting one’s business, and especially the exploitation inherent in it, to the public purse.

It would not do to stretch the connection too far. The slave and the factory worker both exist on the same spectrum of exploited labor, but that did not reduce a wage laborer to the slave’s state. If one wants to construct a scale of horrors to contain both, almost any slave would have things vastly worse than any white worker. No markets existed for the sale of white children. A factory owner might get away with raping a female employee, but the ability to do so did not come built into the value of her labor.

Returning to the quote, it brought to mind where William and Ellen Craft shared details of the Georgia slave code:

Any person who shall maliciously dismember or deprive a slave of life, shall suffer such punishment as would be inflicted in case the like offense had been committed on a free white person, and on the like proof, except in case of insurrection of such slave, and unless SUCH DEATH SHOULD HAPPEN BY ACCIDENT IN GIVING SUCH SLAVE MODERATE CORRECTION. [Emphasis in original.]

and

If any slave, who shall be out of the house or plantation where such slave shall live, or shall be usually employed, or without some white person in company with such slave, shall REFUSE TO SUBMIT to undergo the examination of ANY WHITE person, (let him ever be so drunk or crazy), it shall be lawful for such white person to pursue, apprehend, and moderately correct such slave; and if such slave shall assault and strike such a white person, such slave may be LAWFULLY KILLED.

The interaction between an unarmed black person and a white authority figure (any white back then, any policeman or other armed white person now) which ends with the black person dead and the white entirely above scrutiny remains among our traditions.

Whenever one of these incidents hits the news, one has no trouble at all finding white people absolutely certain that the white person acted entirely reasonably. Even so much as an investigation seems to ask too much to them. After all, the victim stood exactly as tall as the killer. He had an abusive father. He committed some petty crime which we do not punish with death. He did not comply quickly enough. Once or twice, one might write off to simple differences of opinion. When it happens all the time, I don’t know how one can dismiss the notion that white supremacy has done its work.

We don’t take pictures of lynchings and make them into postcards like we used to, but those white bystanders remind me strongly of the crowds in the background. They didn’t all take part in the killing directly, but each one had no problem standing by and watching. Each comfortably faced the camera, expressing their proud approval of the act. Each helped make the killing possible and ensure the guilty walked free. We don’t take those pictures anymore, but some of us still happily stand in the background. If the polls on the subject have it right, most of white America does.

Having the good sense to choose our white skin, we have that privilege. Other people do not. We chose blackness for them and enforce the consequences of our choice. Would could be wrong with that? People killed? Mark Twain had the answer for that, in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Huck comes up with a lie about how he came on a steamboat, but the boat had some difficulties:

I didn’t rightly know what to say, because I didn’t know whether the boat would be coming up the river or down. But I go a good deal on instinct; and my instinct said she would be coming up—from down towards Orleans. That didn’t help me much, though; for I didn’t know the names of bars down that way. I see I’d got to invent a bar, or forget the name of the one we got aground on—or—Now I struck an idea, and fetched it out:

“It warn’t the grounding—that didn’t keep us back but a little. We blowed out a cylinder-head.”

“Good gracious! anybody hurt?”

“No’m. Killed a nigger.”

“Well, it’s lucky; because sometimes people do get hurt.

Nobody got hurt; not to Huck and not to Aunt Sally. Sometimes people do get hurt, but not that time. Sometimes the police do make mistakes, but neither in these incidents nor any others, when the victim had the wrong color picked out for him. Or so we tell ourselves. Whiteness brings the privilege of surprise a few times a year when one hits the news. We do not live with that reality, even if it takes place all around us. We let other people live with it and in so doing help ensure that some of them don’t.

You must be logged in to post a comment.